By Bernice Lerner and Kathleen Stone

Mother’s Day is about more than Hallmark cards, and gifts and meals of appreciation. For those of us who have reached a certain age, it can be a time to reflect—a moment to pause and consider the ways in which our lives, perhaps even our career trajectories, have been influenced by a particular woman. As a writer, I realize that the seeds of my latest book were planted by my mother long before she or I had an inkling of what I would do with the information she shared.

When I was fourteen—the age she was when she was ousted from her home by Hungarian gendarmes—my mother told me about the two death camps she endured: Auschwitz-Birkenau and Bergen-Belsen. The telling came about organically, following many conversations about her childhood and post-war years. It occurred in the basement of our suburban home, where I watched her iron laundry. The evening my mother put down the iron, bent forward, stretched her arms out behind her, and demonstrated how she, half dead herself, dragged skeletal beings to a mass grave, she unknowingly planted the seed that would become my dual biography of her and a British army officer.

I didn't start that book for another 50 years. Only after authoring several other works and reading all I could about the circumstances she endured, did I arrive at an approach to writing about my mother—I would portray her as this young girl who by luck and smarts survived the maelstrom. And because her luck was shaped in part by the compassionate British officer who led the relief of Bergen-Belsen in 1945, when she was nearly dead, I decided to tell his story too.

Impactful stories are conveyed from one generation to the next, but how and when? Not always by the hearth or at the dinner table. Often this happens while the teller is performing some task. No agenda, no conscious imparting of lessons or instruction. Like me, Kathleen Stone, my friend and fellow writer, heard stories of her mother’s life before children in their basement laundry room. (We were amazed when we realized that some of our strongest memories of mother-daughter conversations came from the laundry room.)

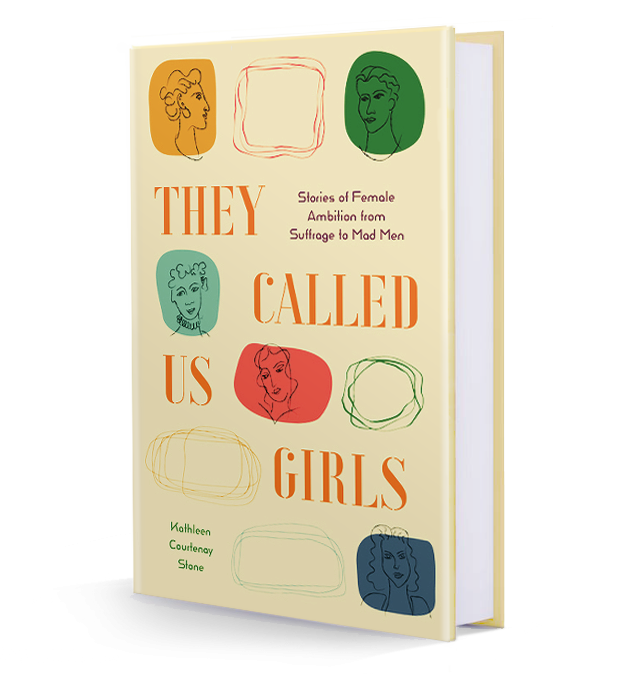

Kathleen’s book—about seven women who had careers in the mid-twentieth century in male-dominated professions—grew out of her interest in women who had jobs similar to her lawyer father. But as she interviewed women for her book, she came to a new appreciation of how her stay-at-home mother influenced her.

Before having children, Kathleen’s mother worked at IBM, training customers on their new office equipment. That business-woman persona never left her. As a mother, she directed Kathleen in clear ways. She recommended books, took her to museums, and insisted she get a good education. She gave her the feeling that a woman could and should take initiative, and not only within the home.

My mother wanted me to have a career but did not know enough to guide or support me. When my children were young, I worked as a college administrator and earned a doctorate. Academia and publishing were foreign worlds to my mother.

She did, however, come from a family where women played vital roles. Her grandmother and mother were both resourceful (e.g., in lean times, her mother could make a nourishing soup out of caraway seeds) and respected businesswomen in the town of Sighet, Transylvania. In the decade after the war, my mother tried to attend school and prepare for a career, but she suffered setbacks—relapses of the tuberculosis she contracted in Bergen-Belsen.

She was, nevertheless, physically adventuresome. As a child, I watched her step outside in protective clothing to take down a wasps' nest on our porch. She fixed whatever broke and climbed high up a ladder to paint the exterior of our house (astonishing the neighbors).

My mother also had an aptitude for sales—she helped my father in his butcher business and then worked for Bloomingdale’s. Kathleen’s mother hewed more to an executive role. She always had a yellow legal pad and a pen, making lists for the family and for several volunteer activities where she had a leadership role. Once her kids were grown, she and a friend started a business helping other women find jobs. Even in her role as a neighborhood mom, she projected the air of being a businesswoman.

When Kathleen went to law school, she knew she was following her father’s career path. But as she worked on her book, she thought about how women become who they are, about both parents’ influences. In her book's epilogue, she realizes that mothers play an incredibly important, and often under-appreciated, role in their daughters' development. If her mother were here today, she would be pleased, even amazed, to read that her daughter had arrived at that understanding.

My mother never expected me to write a book about her. But together—she by telling, me by recording her words—we rescued murdered relatives from oblivion. Through her point-of-view, I was able to describe what happened to tens of thousands, including her iconic peer, Anne Frank. My book, in many ways, is our joint project.

On Mother’s Day, we may reflect with some regret on what we wish had been. Kathleen wishes that her mother was here to see her as a mother herself, who has steered her life according to their long-ago conversations in the laundry room.

I wish I had absorbed more from my mother, who loves opera and classical music and who speaks six languages.

Mother’s Day is an apt time to wonder how our work may have been influenced—in large and the subtlest of ways—by our multi-dimensional mothers.

No comments:

Post a Comment