Guest blog by Nina Murray: A Birthday Wish for the National Poetry Month

My birthday falls during the National Poetry Month in the US. I also happen to be a poet, so when people send me texts, presents, and other nice things for my birthday, I feel like poetry and poets ought to get some of the glow of the attention in which I bask. So this year, I asked my faithful Instagram followers and friends to make it a #helpoutapoet day and post a review of a poetry book they’ve read.

The National Endowment for the Arts found that poetry readership doubled between 2013 and 2018 to a total of 28 million adults, news that was hailed as “

dramatic.” The surveys used in the study that produced this number did not differentiate between having read a poem or a book of poetry.

The

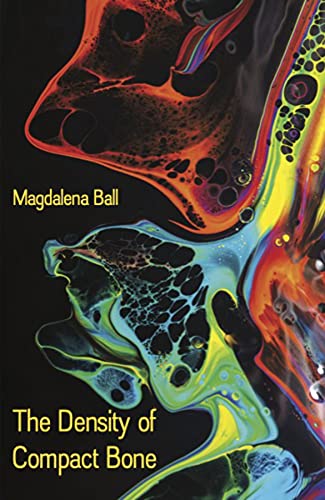

Sealey Challenge arrived in 2017, and poets rejoiced again. After all, if people commit to reading 31 books of poetry in 31 days, that ought to do wonders for the art form. The challenge is a beautiful, spontaneous, powerful thing. It is also very hard, and I don’t even dare take it on. I only read half a dozen poetry collections last year. I reviewed all of them—on blogs, for literary journals, and on Goodreads and Amazon. This is my commitment: to review every book of poetry I read. Here’s why.

Americans, despite the hand-wringing we have all heard, are still reading, and the COVID-19 occasioned lockdown is likely to boost the numbers of books read per person.

What they are reading is a bit harder to pin down. The Census Bureau and the National Endowment for the Arts have been tracking reading trends since 1982. Back then, 56.9 percent of respondents said they had read a work of “creative literature” in the previous twelve months. In 2002, that figure fell to 46.7. In 2017, the most recent data available, 57 percent reported they “read books not required for work or school,” but only

42 percent specifically reported reading “novels or short stories”. Of the millions of books published in the US each year, most that make it into the hands of the readers fall into mystery/thriller and romance categories. When Publishers Weekly did the math for 2020, they found that four out of top-ten selling titles were fiction.

Before a book ever makes it onto a Barnes&Noble shelf with a glossy cover and a hefty price tag, it has to be sold six times, literally and figuratively. The author has to sell the manuscript to the agent. The agent has to sell it to the publisher, specifically, to the acquisitions editor. If the acquisitions editor has to get an editorial board’s approval, that’s three. Four: the acquisitions talks up the book to the marketing department. Five: marketing goes on the road to sell books to the wholesalers or reps. Six: the buyers at Barnes&Noble “sell” the book to the merchandisers who decide where in the store it goes, whether it gets a separate display, whether it is allowed to be placed flat on the shelf or just slipped, spine out, between its fellows. By the time you, dear reader, come into the bookstore with your preciously limited disposable income ($24.95 per year per “consumer unit” in 2019, which buys you one hardcover edition) a large group of professionals has labored for months to ensure that your judgement of their product is quick (because, after all, your attention span is shortened by all that visual media you consume) and positive.

In the scrappy world of independent authors (previously known as self-publishing), the game is all about the numbers because that’s what algorithms understand. Instead of sending hundreds of queries to literary agents or publishers, the author recruits beta-readers. The author sets a release date and distributes advance copy to more readers, of whom at least a few, one hopes, have high visibility to Amazon. The author, inevitably, gets spam-sounding emails from people who offer to read and review his/her book for a small fee. There are give-aways to manage. Ad campaigns to design. The Eye of Sauron... I mean, the Amazon algorithm to catch.

Let’s take a closer look.

The author wrote a query letter to the agent (‘the pitch’). The author chose carefully and wrote to the agent who specializes in the kind of book the author has written. Since the author did his/her homework, the agent considered the manuscript carefully, and if it fit with what the agent usually represents and was a competent piece of craftsmanship, the agent took it on and eventually called an editor. Obviously, the agent didn’t call just any editor – he/she has done her homework too, and only calls editors who publish the kind of books the agent represents. The editor wrote an internal memo to the board or to the marketing department. In it, he/she certainly mentioned how the book fits with the existing list of previously published titles.

On the basis of these, marketing wrote the back-cover blurb. The author suggested other authors who might provide “advance praise”. Marketing also zeroed in on the keywords under which the book is catalogued in the Library of Congress and on bookstore shelves: Fiction—Women—Pregnancy. Or, Omaha, NE—Fiction. These categories help retailers categorize those millions of books that come to them each year; it is understandable that one would want them to be as narrow as possible, to minimize competition in each niche. Also, when you are looking for that belated gift for your 12-year-old niece who loves sharks, they save the day: Marine life—Pre-teen—Non-fiction. Done.

What all this preparation, all these keywords, blurbs and advance praises will never tell you, is whether the book you are holding in your hands is about to change your world. They won’t tell you if you’re holding a masterpiece, the defining work of our times, the next great one. They can’t. The number of titles published every year is growing, and the portion of the disposable income spent on books is falling. The resources required to attract your, dear reader, attention to a particular book far outweigh those necessary to produce it. The result is further compartmentalization of the supply. This means, basically, that editors and agents are narrowing their areas of acquisition, just as bookstores are fitting more keywords onto a single shelf, and Amazon’s algorithms try to match your reading preference to your choice of color for the bath towels.

A medium-sized publishing house may not consider any fiction other than novels set in a particular region, such as the Midwest. Should one of them happen to be the next literary revolution, its success will still depend on the amount of resources the marketing department can throw behind it, and those resources are always limited—at smaller presses, there simply isn’t that much money to go around, and at the bigger presses the cost of the author’s advance can swallow a big chunk of a book’s budget.

How, then, are we readers to choose the books we buy in search of inspiration, enlightenment, or simply entertainment? How do we know we are not wasting our $24.95? Or even $2.95 for a Kindle edition?

If it’s money you are worried about, the answer is easy: public libraries are excellent, thrift stores are awash in well- and less-known gems, and Little Free Libraries are adorable.

If, however, you would like to know what you

should read next, for reasons of emotional, dramatic, or comic power, you might be at sea. You might—and very well should—turn to places that publish reviews (and I don’t mean Goodreads). In the interest of cutting costs, newspapers across the country have cut book review staff and discontinued relationships with free-lance writers. One no longer has the luxury of making a living as a literary critic (remember those?). Reviewers are volunteers, and just like other volunteers they do this work because they believe in it. They believe that when they sit down with a book, read it with an open mind, and give you their honest opinion, they do something that no one else will.

About the author: Nina Murray, poet, translator

Nina Murray was born and raised in the Western Ukrainian city of Lviv. She holds advanced degrees in linguistics and creative writing. She is the author of the poetry collection Alcestis in the Underworld (Circling Rivers Press, 2019) as well as chapbooks Minimize Considered (Finishing Line Press, 2018), Minor Heresies (Heartland Review Press, 2020), and Damascus Electric (Pen & Anvil Press, 2020). Her translations from Russian and Ukrainian include Peter Aleshkovsky's Stargorod, Oksana Zabuzhko's Museum of Abandoned Secrets, and Oksana Lutsyshyna's Ivan and Phoebe (forthcoming from Deep Vellum).

Nina Murray was born and raised in the Western Ukrainian city of Lviv. She holds advanced degrees in linguistics and creative writing. She is the author of the poetry collection Alcestis in the Underworld (Circling Rivers Press, 2019) as well as chapbooks Minimize Considered (Finishing Line Press, 2018), Minor Heresies (Heartland Review Press, 2020), and Damascus Electric (Pen & Anvil Press, 2020). Her translations from Russian and Ukrainian include Peter Aleshkovsky's Stargorod, Oksana Zabuzhko's Museum of Abandoned Secrets, and Oksana Lutsyshyna's Ivan and Phoebe (forthcoming from Deep Vellum).

She speaks Russian, Ukrainian, Spanish, Lithuanian, and English.

.jpg)